One of the great things about working in a library is that you get to track the books that everyday readers -- not reviewers, prize panels, or critics -- genuinely love, titles like The Nightingale by Kristin Hannah or All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr or, recently, just about every title released by Frederik Backman. I always take note of these books, so I can recommend them to others but also so I can eventually get to them myself. Ordinary Grace by William Kent Krueger is one such book.

Published in 2013, it's beautifully written, warm-hearted, poignant, and suspenseful. It's a standalone work by an author best known for his Cork O'Connor mystery series set up in northern Minnesota, a series that is also well-loved. Krueger is known for his evocative descriptions of landscapes and places and his incorporation of Native American characters and culture into his books, both features prominent in Ordinary Grace.

The novel relates the events of one hot summer in Minnesota in 1961. Kennedy is president and the mood of the country hopeful, but the sleepy town of New Bremen experiences a series of unfortunate -- no, make that tragic -- events.

We see these incidents unfold through the eyes of thirteen-year-old Frank Drum, son of the town's Methodist minister, whose family is a happy one despite the usual assortment of disappointments and challenges: Frank's mom, an aspiring singer, isn't thrilled to have landed in a backwater leading a church choir; Frank's spiritually gifted younger brother struggles with a stutter; Frank's brilliant older sister bears the scars of a surgically repaired hairlip; Frank's father conceals psychic scars from the second World War. All five family members are very well drawn and the large supporting cast of townspeople is rendered just as skillfully.

Frank begins the summer a regular kid, pre-occupied with baseball and the usual early-teen boy things. Then, a series of three unrelated deaths occur that cause his world to crack open. These deaths set off a chain of further unfortunate events, perhaps to an extent that stretches the reader's credulity just a bit. I was willing to suspend my disbelief because Krueger writes so well, in such convincing detail, and with so much compassion. He keeps the reader turning pages too, to find out who did what to whom. But what he really examines through these plot detonations is the harsh truth that awful things do happen to good people, but those people can find the strength and courage -- and enough ordinary grace in this world -- to go on.

There's nothing saccharine about Krueger's cast or facile in the ways they cope in the aftermath. Krueger offers no easy answers. His people are flawed, they spend nights in the drunk tank, they make big mistakes, they can't always forgive. But they are caring and authentic and thoughtful. In the end there is something so life-affirming in the world Krueger creates. His book is exquisitely graceful.

~ Ann, Adult Services

Showing posts with label Ann. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Ann. Show all posts

Sunday, October 30, 2016

Sunday, October 16, 2016

Staff Audiobook Review: The Boys of My Youth by Jo Ann Beard

I don't know why it has taken me almost twenty years to notice the essay collection The Boys of My Youth by Jo Ann Beard and read (or, rather, listen to) it. First published in 1998 to a loud chorus of high praise, the book led to Beard's being awarded both a Guggenheim Fellowship and a Whiting Award.

The collection constitutes a patchwork memoir. At the time of its publication, it drew most attention for one piece, previously published in the The New Yorker. That essay, "The Fourth State of Matter," is a meticulous and heartbreaking narrative of the 1991 mass shooting at the University of Iowa by a disturbed physics graduate student, which claimed six lives, including the shooter's, and left another victim paralyzed from the neck down. The narrative of that horrific event is woven into finely-grained depictions of the author's own domestic woes: a dying dog and dissolving marriage. It makes for a poignant weave that in no way diminishes the relative magnitude of the shooting.

Jo Ann Beard, a graduate of the University of Iowa and of Iowa's MFA writing program, was an editor of the physics department's academic journal at the time of the shootings and very close to several of the victims. She had left the office early that day to tend to her old, ailing pet. At home, her phone soon began ringing off the hook. In her essay, which, like all the essays in the book, is precisely detailed, wryly but not inappropriately funny, and strikingly well-written, Beard conjures the tragedy in such a vividly authentic way that I listened, heart in throat, grieved for the victims, and glimpsed the scale of the incident's extensive collateral damage.

Other essays breathe life into Beard's early childhood, adolescence, high school and college beaus, and her ultimately failed marriage. She presents her life in a non-linear way, each essay forming its own discrete story. Beard is a master of the exquisite detail and one has to wonder at her powers of recollection and suspect some poetic license in the telling. Usually I'm pretty particular about strict truth in the memoirs I read, but this book is so artfully written and profoundly affecting that I was willing to park my skepticism at the door.

Her masterful handling of a seemingly infinite number of precise details results in one stunning piece after another. Her mother, especially, is finely-wrought and we see exactly where Beard gets her cleverness and wry humor, which are powerful mechanisms in a book that depicts so much dysfunction, disorder, death, and divorce. As I listened, my heart's pangs were frequently accompanied by my laughter. I've rarely experienced such a seamless blend of humor and sorrow.

The author reads this audiobook and does a serviceable job. She sounds a little hypnotized, but she has written a hypnotic book so maybe it's fitting. And her deadpan delivery of very funny material only accentuates the humor. Jo Ann Beard is one sharp woman and I highly recommend this audiobook.

~Ann, Adult Services

The collection constitutes a patchwork memoir. At the time of its publication, it drew most attention for one piece, previously published in the The New Yorker. That essay, "The Fourth State of Matter," is a meticulous and heartbreaking narrative of the 1991 mass shooting at the University of Iowa by a disturbed physics graduate student, which claimed six lives, including the shooter's, and left another victim paralyzed from the neck down. The narrative of that horrific event is woven into finely-grained depictions of the author's own domestic woes: a dying dog and dissolving marriage. It makes for a poignant weave that in no way diminishes the relative magnitude of the shooting.

Jo Ann Beard, a graduate of the University of Iowa and of Iowa's MFA writing program, was an editor of the physics department's academic journal at the time of the shootings and very close to several of the victims. She had left the office early that day to tend to her old, ailing pet. At home, her phone soon began ringing off the hook. In her essay, which, like all the essays in the book, is precisely detailed, wryly but not inappropriately funny, and strikingly well-written, Beard conjures the tragedy in such a vividly authentic way that I listened, heart in throat, grieved for the victims, and glimpsed the scale of the incident's extensive collateral damage.

Other essays breathe life into Beard's early childhood, adolescence, high school and college beaus, and her ultimately failed marriage. She presents her life in a non-linear way, each essay forming its own discrete story. Beard is a master of the exquisite detail and one has to wonder at her powers of recollection and suspect some poetic license in the telling. Usually I'm pretty particular about strict truth in the memoirs I read, but this book is so artfully written and profoundly affecting that I was willing to park my skepticism at the door.

Her masterful handling of a seemingly infinite number of precise details results in one stunning piece after another. Her mother, especially, is finely-wrought and we see exactly where Beard gets her cleverness and wry humor, which are powerful mechanisms in a book that depicts so much dysfunction, disorder, death, and divorce. As I listened, my heart's pangs were frequently accompanied by my laughter. I've rarely experienced such a seamless blend of humor and sorrow.

The author reads this audiobook and does a serviceable job. She sounds a little hypnotized, but she has written a hypnotic book so maybe it's fitting. And her deadpan delivery of very funny material only accentuates the humor. Jo Ann Beard is one sharp woman and I highly recommend this audiobook.

~Ann, Adult Services

Tags:

Ann,

Audiobooks,

Family,

FY17,

Iowa Books,

Memoir,

Midwest,

Staff Reviews

Sunday, October 2, 2016

Staff Review: Lafayette in the Somewhat United States by Sarah Vowell

Anyone who has read one of Sarah Vowell's books knows how funny she is. Laugh-out-loud funny at times. But when it comes to American history, she knows her stuff. Hers is a fresh take on what we all learned in school: the Puritans on the Mayflower, our past presidents, the Salem witch trials, the Civil War. Sometimes she goes farther afield: in one book, Unfamiliar Fishes, she explores the events leading up to the U.S. annexation of Hawaii. Vowell is snarky, irreverent, and a whole lot of fun. Always droll, never dull, often remarkably astute, she breathes new life into old stories.

In Lafayette in the Somewhat United States, her most recent book, she really shows off her chops. I can't imagine how much reading, research, and travel must have gone in to writing this book. Vowell seems at ease with all the major battles of the Revolutionary War, which went on for eight long years, and with all the key players, from military leaders like George Washington and Benedict Arnold to members of the Continental Congress. Her focus is on Marie-Joseph-Paul-Yves-Roch-Gilbert du Motier, better known as the Marquis de Lafayette, a 19-year-old French aristocrat who crossed the ocean in 1776 to take up the cause of American liberty. Swashbuckling and debonair, he became not only a highly capable general but a sort of surrogate son to Washington, who was crazy about him.

The book opens with Lafayette's return to the U.S. in 1824, at age 67, for a grand tour of all (by then) 24 states. Americans still adored him for his contributions to the cause of freedom and he was greeted by cheering crowds everywhere he went. By that time, he had not only survived the American Revolution (he was wounded at the Battle of Brandywine) but also emerged neck intact from "the Terror" -- the bloody chaos of the French Revolution, with its flames, pitchforks, and flashing guillotine. Vowell then turns back in time to the trajectory of the American Revolution, interspersing her own clever assessment of historical events with anecdotes about people she meets and sites she visits while conducting her extensive research.

She is so amiable in her snarkiness that I always finish her books wishing I could hang out with her. I also laugh and learn a lot along the way. By the close of this one, I understood for the very first time just how much the French helped us win the War of Independence (something we might have done well to remember during the Freedom-fries fiasco of 2003) and I had a much better appreciation of the reason so many American cities, towns, counties, hills, rivers, bridges, parks, schools, boats, and buildings were named in honor of Gilbert du Motier, the Marquis de Lafayette.

Cautionary Note: I better add a note about the audio version. When you hear Vowell for the first time (she narrates her own books), you may well be a bit turned off, especially if you're just coming off a super-fine audiobook narrator. For all that Vowell's such a big radio personality and has done so much voice and acting work, her high-pitched, lispy, little-kid voice can be dismaying, but I promise if you power through the first chapter or two, you'll cease to notice. It won't bother you at all. You may even come to find it endearing.

~Ann, Adult Services

In Lafayette in the Somewhat United States, her most recent book, she really shows off her chops. I can't imagine how much reading, research, and travel must have gone in to writing this book. Vowell seems at ease with all the major battles of the Revolutionary War, which went on for eight long years, and with all the key players, from military leaders like George Washington and Benedict Arnold to members of the Continental Congress. Her focus is on Marie-Joseph-Paul-Yves-Roch-Gilbert du Motier, better known as the Marquis de Lafayette, a 19-year-old French aristocrat who crossed the ocean in 1776 to take up the cause of American liberty. Swashbuckling and debonair, he became not only a highly capable general but a sort of surrogate son to Washington, who was crazy about him.

The book opens with Lafayette's return to the U.S. in 1824, at age 67, for a grand tour of all (by then) 24 states. Americans still adored him for his contributions to the cause of freedom and he was greeted by cheering crowds everywhere he went. By that time, he had not only survived the American Revolution (he was wounded at the Battle of Brandywine) but also emerged neck intact from "the Terror" -- the bloody chaos of the French Revolution, with its flames, pitchforks, and flashing guillotine. Vowell then turns back in time to the trajectory of the American Revolution, interspersing her own clever assessment of historical events with anecdotes about people she meets and sites she visits while conducting her extensive research.

She is so amiable in her snarkiness that I always finish her books wishing I could hang out with her. I also laugh and learn a lot along the way. By the close of this one, I understood for the very first time just how much the French helped us win the War of Independence (something we might have done well to remember during the Freedom-fries fiasco of 2003) and I had a much better appreciation of the reason so many American cities, towns, counties, hills, rivers, bridges, parks, schools, boats, and buildings were named in honor of Gilbert du Motier, the Marquis de Lafayette.

Cautionary Note: I better add a note about the audio version. When you hear Vowell for the first time (she narrates her own books), you may well be a bit turned off, especially if you're just coming off a super-fine audiobook narrator. For all that Vowell's such a big radio personality and has done so much voice and acting work, her high-pitched, lispy, little-kid voice can be dismaying, but I promise if you power through the first chapter or two, you'll cease to notice. It won't bother you at all. You may even come to find it endearing.

~Ann, Adult Services

Sunday, August 21, 2016

Staff Review: My Brilliant Friend and The Story of a New Name by Elena Ferrante

Ferrante herself is a mystery woman. No one knows who she is, what she looks like, or where she lives. This in itself, in an age of massive media attention to every big new thing, is remarkable and might reasonably be perceived as a sort of media blitz of its own (search "Elena Ferrante's identity" and you get over 100,000 results). Everyone is speculating, guessing, even claiming to have found her. If she remains elusive, it will be a marvel.

So, what do I think of the quartet halfway in? I'd have to say I like them, I dislike them, and I can't seem to put them down. Ferrante creates an exquisitely detailed world that spans decades and brings Naples to life politically and culturally. The story line follows the friendship of two Neapolitan girls born just after World War II. They're five or six as My Brilliant Friend begins and about twenty as the second novel, The Story of a New Name, concludes (they'll be going on seventy by the end of the series).

Elena and Lila were born in the same poor, violent neighborhood in Naples, where husbands beat wives, brothers beat sisters, parents beat kids, and the typical hissed threat is "Do that again and so help me God I will kill you." At that time in Italy, feminism wasn't a concept nor was divorce legal; the lives of many Italian women were bleak. Many men's lives weren't so great either.

Elena, the studious good girl, and Lila, the rebel, are both unusually bright but only Elena completes high school and even goes on to college. Over the years the girls' friendship waxes and wanes, sometimes breaking off tumultuously. Events play out within a large cast of neighborhood characters: family members, schoolmates, boyfriends, teachers, parents, shopkeepers, and the notorious Solara family, linked to the Camorra (Neapolitan organized crime), whose members control the neighborhood through loansharking, extortion, threats, beatings, and even murder.

It's not the novels' gritty setting with its violence and corruption that, at times, turns me off. It's the wildly unpredictable nature of Elena and Lila's friendship. At times Lila's a true-blue friend and at other times she behaves in unpredictable, despicable, and cruel ways. She hurts Elena again and again. Of course, it can certainly be said that she hurts herself more. Elena gets in a few licks too, at one point dumping a box of Lila's journals, painstakingly written over the years and entrusted to Elena's care, into the Arno River. Their breaches can make for tough reading.

Reviewing this series in the Financial Times, the novelist Claire Messud wrote, "I end up thinking that the people who don't see Ferrante's genius are those who can't face her uncomfortable truths: that women's friendships are as much about hatred as love . . . ." I guess I can't -- or don't -- accept that particular "truth," but I also can't stop reading the novels; I'm just about to start book three, Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay. Ferrante has created a series that's powerfully compelling. And, in the end, maybe my love/hate relationship with it is fitting. After all, Lila and Elena love and hate each other for over sixty years. Maybe I'm just not Neapolitan enough to get it.

~Ann, Adult Services

Tags:

Ann,

Audiobooks,

friendship,

FY17,

History,

Italy,

Staff Reviews,

Women

Sunday, July 31, 2016

Staff Review: Valiant Ambition by Nathaniel Philbrick

I have this thing for Benedict Arnold. I've been fascinated by him for years, primarily because of his amazing and heroic slog to Quebec through the wilderness of Maine and Canada at the start of the Revolutionary War (you can read all about that difficult and dangerous journey in Through a Howling Wilderness by Thomas Desjardin). By the time Arnold finally reached Quebec, his force of 1,100 troops had been reduced to 600 starving men.

Back then Arnold was well on his way to becoming the brightest star in the American military firmament, a reputation he continued to build with brilliant feats throughout the first battles of the war. I just hate that after amassing all that well-earned glory, he wound up committing treason. His name is now synonymous with "dirty, rotten scoundrel," the worst in U.S. history.

The highly-readable popular historian Nathaniel Philbrick tackles Arnold's tragic trajectory from "American Hannibal" to despicable traitor in his new book, Valiant Ambition. Philbrick juxtaposes Arnold's career with that of his commander, George Washington, who, unlike Arnold, made quite a few tactical mistakes and bad judgment calls in his early days as leader of the Continental army, but over the course of the war grew into a brilliant leader of the highest character. Arnold's character, on the other hand, had its flaws.

While Philbrick can't redeem Benedict Arnold, Valiant Ambition does help us to understand (and maybe even sympathize with) his eventual treason by relating how shabbily Arnold was treated by the Continental Congress and by other politicians and military leaders seeking their own advantage at his expense. Arnold poured his own fortune into the American cause and was never compensated by Congress. He was passed over repeatedly for promotion. He was seriously wounded twice in the service of his country, while many, many others sacrificed nothing, seemed indifferent to the outcome of the war, and were more concerned with grandstanding, profiteering, and personal advancement. Readers soon learn that there's a whole lot more to our founding story than we learn in school and much of it is pretty unsavory.

Ironically, Arnold's loss of faith in the integrity of the American effort and his ultimate act of treason united the country, forcing people to shake off their lethargy and take note of the fact that the greatest threats to the nation were likely to come not from without but from within. It might even be said that had Arnold not committed treason, we might well have lost the Revolutionary War.

~ Ann, Adult Services

Back then Arnold was well on his way to becoming the brightest star in the American military firmament, a reputation he continued to build with brilliant feats throughout the first battles of the war. I just hate that after amassing all that well-earned glory, he wound up committing treason. His name is now synonymous with "dirty, rotten scoundrel," the worst in U.S. history.

The highly-readable popular historian Nathaniel Philbrick tackles Arnold's tragic trajectory from "American Hannibal" to despicable traitor in his new book, Valiant Ambition. Philbrick juxtaposes Arnold's career with that of his commander, George Washington, who, unlike Arnold, made quite a few tactical mistakes and bad judgment calls in his early days as leader of the Continental army, but over the course of the war grew into a brilliant leader of the highest character. Arnold's character, on the other hand, had its flaws.

While Philbrick can't redeem Benedict Arnold, Valiant Ambition does help us to understand (and maybe even sympathize with) his eventual treason by relating how shabbily Arnold was treated by the Continental Congress and by other politicians and military leaders seeking their own advantage at his expense. Arnold poured his own fortune into the American cause and was never compensated by Congress. He was passed over repeatedly for promotion. He was seriously wounded twice in the service of his country, while many, many others sacrificed nothing, seemed indifferent to the outcome of the war, and were more concerned with grandstanding, profiteering, and personal advancement. Readers soon learn that there's a whole lot more to our founding story than we learn in school and much of it is pretty unsavory.

Ironically, Arnold's loss of faith in the integrity of the American effort and his ultimate act of treason united the country, forcing people to shake off their lethargy and take note of the fact that the greatest threats to the nation were likely to come not from without but from within. It might even be said that had Arnold not committed treason, we might well have lost the Revolutionary War.

~ Ann, Adult Services

Sunday, July 10, 2016

Staff Review: The Summer Before the War by Helen Simonson

If you're a fan of Jane Austen and other 19th century novelists of life and love in quaint villages of long-ago England, you should not miss The Summer Before the War by Helen Simonson. Although it begins in 1914, on the eve of World War I, it quickly put me in mind of those earlier authors, with its exquisite village setting, its jumble of aristocrats and commoners, and its lavish period detail about dress, food, furniture, customs, and manners.

The novel begins slowly, as a charming tale of coastal village life at "the end of England's brief Edwardian summer." The weather has rarely been so glorious. Young, pretty, free-thinking -- and penniless -- Beatrice arrives to take her controversial place as the local grammar school's new Latin master, a position that until now has always been filled by a man. Her conditional hire situates Beatrice within a large cast of characters and allows Simonson to tackle the subject of the subjugation of women in the early twentieth century, which she succeeds at doing very well without being heavy-handed.

The rumblings of war draw closer however, Belgian refugees soon arrive in the village, and before long all are swept up in the years of bloody and tumultuous fighting that will eventually claim over 17 million lives, wound 20 million more, and end forever many of the old European ways of living. Despite the chaos into which the period descends, Simonson succeeds in bringing history vividly to life and her characters and story to satisfying conclusions.

Simonson's mastery of her material is astonishing, especially considering this is only her second novel, the first being the highly acclaimed and equally delightful Major Pettigrew's Last Stand. She's a natural born storyteller. Her characters rarely hit a false note, historical detail is fluidly rendered, and the writing is well-crafted, witty, and intelligent. There's no treacle here either; certain scenes are hard to take. People suffer atrocities, reputations are hurt, class cruelty abounds, and a few characters do not survive to the end. In constructing this intricate tale of love, class, and war, Simonson never settles for confection but hews to the genuine and authentic.

~ Ann, Adult Services

The novel begins slowly, as a charming tale of coastal village life at "the end of England's brief Edwardian summer." The weather has rarely been so glorious. Young, pretty, free-thinking -- and penniless -- Beatrice arrives to take her controversial place as the local grammar school's new Latin master, a position that until now has always been filled by a man. Her conditional hire situates Beatrice within a large cast of characters and allows Simonson to tackle the subject of the subjugation of women in the early twentieth century, which she succeeds at doing very well without being heavy-handed.

The rumblings of war draw closer however, Belgian refugees soon arrive in the village, and before long all are swept up in the years of bloody and tumultuous fighting that will eventually claim over 17 million lives, wound 20 million more, and end forever many of the old European ways of living. Despite the chaos into which the period descends, Simonson succeeds in bringing history vividly to life and her characters and story to satisfying conclusions.

Simonson's mastery of her material is astonishing, especially considering this is only her second novel, the first being the highly acclaimed and equally delightful Major Pettigrew's Last Stand. She's a natural born storyteller. Her characters rarely hit a false note, historical detail is fluidly rendered, and the writing is well-crafted, witty, and intelligent. There's no treacle here either; certain scenes are hard to take. People suffer atrocities, reputations are hurt, class cruelty abounds, and a few characters do not survive to the end. In constructing this intricate tale of love, class, and war, Simonson never settles for confection but hews to the genuine and authentic.

~ Ann, Adult Services

Sunday, June 12, 2016

Staff Review: The Road to Little Dribbling by Bill Bryson

It's been twenty years since Iowan-turned-Englishman Bill Bryson wrote Notes from a Small Island, relating his 1995 trip around Great Britain. The book wound up being the most successful travel book ever, with 2.5 million copies sold to date. So, Bryson's publisher, with "little glinting pound signs" in his eyes, suggested Bryson do it again, with a different itinerary this time of course.

The result is The Road to Little Dribbling, written just as Bryson passes his test to become a British citizen (his wife is English). His itinerary this time roughly follows the so-called Bryson Line, a line he invents linking the two most far-flung points in Britain, Bognor Regis and Cape Wrath, as the crow flies. Bryson perambulates this route, with numerous side-trips to London (his favorite city in the world, a city with more green space than any other in Europe).

His travel commentary is entertaining and often very funny. Those who have read Bryson know he's a real curmudgeon; this work confirms that his curmudgeonliness has moved to the next level. Some reviewers have called him on this, saying he's become an over-the-top crank, but I found his grousing largely amusing and was more annoyed by his penchant for acting "over the hill" and in his "dotage" (at 63) when it's clear that he is as sharp as ever and can easily walk for miles. Why pretend to be decrepit? Besides, his crankiness is more than offset by the loving tribute he pays throughout the book to the stunning beauty of Britain's natural landscape and to her countless cathedrals, monuments, museums, and other historical sites. Britain's a bottomless treasure trove for art buffs, book lovers, historians, and nature enthusiasts.

Sadly, not all of Britain is doing very well these days. Bryson pays visits to formerly vibrant villages and resort towns now well on their way to dying, leading him to make caustic remarks about the government's austerity measures. In the main though, this book will leave you yearning to cross the Atlantic and see for yourself “how casually strewn with glory Britain is.”

~Ann, Adult Services

The result is The Road to Little Dribbling, written just as Bryson passes his test to become a British citizen (his wife is English). His itinerary this time roughly follows the so-called Bryson Line, a line he invents linking the two most far-flung points in Britain, Bognor Regis and Cape Wrath, as the crow flies. Bryson perambulates this route, with numerous side-trips to London (his favorite city in the world, a city with more green space than any other in Europe).

His travel commentary is entertaining and often very funny. Those who have read Bryson know he's a real curmudgeon; this work confirms that his curmudgeonliness has moved to the next level. Some reviewers have called him on this, saying he's become an over-the-top crank, but I found his grousing largely amusing and was more annoyed by his penchant for acting "over the hill" and in his "dotage" (at 63) when it's clear that he is as sharp as ever and can easily walk for miles. Why pretend to be decrepit? Besides, his crankiness is more than offset by the loving tribute he pays throughout the book to the stunning beauty of Britain's natural landscape and to her countless cathedrals, monuments, museums, and other historical sites. Britain's a bottomless treasure trove for art buffs, book lovers, historians, and nature enthusiasts.

Sadly, not all of Britain is doing very well these days. Bryson pays visits to formerly vibrant villages and resort towns now well on their way to dying, leading him to make caustic remarks about the government's austerity measures. In the main though, this book will leave you yearning to cross the Atlantic and see for yourself “how casually strewn with glory Britain is.”

~Ann, Adult Services

Tags:

Ann,

Audiobooks,

FY16,

Great Britain,

Non-Fiction,

Staff Reviews,

Travel

Sunday, May 29, 2016

Staff Review: Did You Ever Have a Family by Bill Clegg

Did You Ever Have a Family, a debut novel by Bill Clegg, opens with a bang. Literally. A big one. In the scale of the whole wide world, it may not be a cataclysm, but in the more modest scale of family and community it's catastrophic. In an instant the novel's main character loses everyone and everything; she's rendered family-less in the blink of an eye, yet she must find a way to go on. What choice does she have, other than suicide?

Did You Ever Have a Family, a debut novel by Bill Clegg, opens with a bang. Literally. A big one. In the scale of the whole wide world, it may not be a cataclysm, but in the more modest scale of family and community it's catastrophic. In an instant the novel's main character loses everyone and everything; she's rendered family-less in the blink of an eye, yet she must find a way to go on. What choice does she have, other than suicide?By this point you may be thinking this book does not sound like a feel-good read and that you probably ought to avoid it. But that would be a mistake. I found it to be one of the most moving, most human, and ultimately most redemptive novels I've read this past year and I heartily recommend it.

After the opening big bang, Clegg beautifully and succinctly relates not only the incident's aftermath but also years of backstory -- the relationships and events -- that lead to this particular cast of doomed characters being together in one place on the incendiary day. The wider network of relatives, friends, acquaintances, and even service workers affected by the tragedy, closely or tangentially, is painstakingly introduced, person by person within their own chapters, their individual humanities brought to life in a series of exquisite scenes that move from the affluent Connecticut 'burbs of New York City through Montana and Idaho and on to the turbulent coast of the Pacific Northwest.

What is particularly impressive about this novel is the even-handed and compassionate way in which Clegg presents his characters, people of very different income and educational levels, racial backgrounds, sexual preferences, and social standing. The catastrophe at the core of the plot has wounded them all and in their raw vulnerability they slowly rise to the occasion, becoming more rather than less, reaching out to one another, and, in the end, forming new communities based not upon occupation, class, or local reputation, but upon more basic and authentic aspects of being human.

Before tackling fiction, Clegg, a literary agent, wrote two memoirs about his own devastating drug addiction; it seems his descent into the abyss and eventual restoration are serving him well in his fiction.

~Ann, Adult Services

Sunday, May 15, 2016

The Great Reading Challenge: Read a Classic!

"Read a classic novel" is one of the categories in C-SPL's Great Reading Challenge. I decided it was time to read Light in August by William Faulkner, which my son has been urging me to read. So I read it and I'm not sure I'll ever recover.

Light in August may be the grimmest, darkest, most harrowing novel I have ever read. Written in 1932, it examines issues of race, gender, religion, and social class in the American South -- and not in any way that makes you want to re-locate. It's Southern Gothic on steroids. I'm not sure I can recommend it except to say that Faulkner is brilliant, he writes like some higher order of angel (a dark angel, that is), and if you like Cormac McCarthy, you may very well like Faulkner.

If you'd like to check off the Classic Novel box but don't want anything that makes you lose the will to live, here are a few more-upbeat suggestions:

Middlemarch, arguably the greatest novel in the English language,

is George Eliot's masterpiece. The novel examines the lives, struggles,

failures, and redemptions of a fascinating network of characters inhabiting the Midlands town of Middlemarch as the industrial age approaches. Its centerpiece is Dorothea Brooke, a beautiful and intelligent young woman seeking a life of significance at a tough time for women. (George Eliot, by the way, was a woman.) At 800-plus pages, this one is not for the faint of heart but it's worth every minute of the effort.

The Moonstone by Wilkie Collins, who was Charles Dicken's good friend, is often called the first detective novel in English. The Moonstone's crime is the theft of the Tippoo

diamond after the fall of Seringapatam in India in 1799. The Indian element imbues this very British, very Victorian novel, told by way of letters, with an exotic and sinister atmosphere. There's a great cast of characters and as with all good Victorian reads, romance is definitely in the air (or will be once the villain is identified).

often called the first detective novel in English. The Moonstone's crime is the theft of the Tippoo

diamond after the fall of Seringapatam in India in 1799. The Indian element imbues this very British, very Victorian novel, told by way of letters, with an exotic and sinister atmosphere. There's a great cast of characters and as with all good Victorian reads, romance is definitely in the air (or will be once the villain is identified).

Jane Eyre, by Charlotte Bronte, is surely one of the world's most beloved novels. It's one of those classics nobody gripes about having to read. That's because it's got everything: a Gothic atmosphere, an evil orphanage, a clever, bright, unconventional heroine (she's neither gorgeous nor splendidly wealthy), a brooding lord of the manor, a romantic competitor who is lovely and rich, a catastrophic fire, something sinister and creepy in the attic, and more! The intelligent and witty dialogue between Jane, a mere governness, and Mr. Edward Rochester, master of Thornfield Hall, makes for some wonderfully gripping (and, dare I say, romantic?) reading.

~Ann, Adult Services

Light in August may be the grimmest, darkest, most harrowing novel I have ever read. Written in 1932, it examines issues of race, gender, religion, and social class in the American South -- and not in any way that makes you want to re-locate. It's Southern Gothic on steroids. I'm not sure I can recommend it except to say that Faulkner is brilliant, he writes like some higher order of angel (a dark angel, that is), and if you like Cormac McCarthy, you may very well like Faulkner.

If you'd like to check off the Classic Novel box but don't want anything that makes you lose the will to live, here are a few more-upbeat suggestions:

Middlemarch, arguably the greatest novel in the English language,

is George Eliot's masterpiece. The novel examines the lives, struggles,

failures, and redemptions of a fascinating network of characters inhabiting the Midlands town of Middlemarch as the industrial age approaches. Its centerpiece is Dorothea Brooke, a beautiful and intelligent young woman seeking a life of significance at a tough time for women. (George Eliot, by the way, was a woman.) At 800-plus pages, this one is not for the faint of heart but it's worth every minute of the effort.

The Moonstone by Wilkie Collins, who was Charles Dicken's good friend, is

often called the first detective novel in English. The Moonstone's crime is the theft of the Tippoo

diamond after the fall of Seringapatam in India in 1799. The Indian element imbues this very British, very Victorian novel, told by way of letters, with an exotic and sinister atmosphere. There's a great cast of characters and as with all good Victorian reads, romance is definitely in the air (or will be once the villain is identified).

often called the first detective novel in English. The Moonstone's crime is the theft of the Tippoo

diamond after the fall of Seringapatam in India in 1799. The Indian element imbues this very British, very Victorian novel, told by way of letters, with an exotic and sinister atmosphere. There's a great cast of characters and as with all good Victorian reads, romance is definitely in the air (or will be once the villain is identified).Jane Eyre, by Charlotte Bronte, is surely one of the world's most beloved novels. It's one of those classics nobody gripes about having to read. That's because it's got everything: a Gothic atmosphere, an evil orphanage, a clever, bright, unconventional heroine (she's neither gorgeous nor splendidly wealthy), a brooding lord of the manor, a romantic competitor who is lovely and rich, a catastrophic fire, something sinister and creepy in the attic, and more! The intelligent and witty dialogue between Jane, a mere governness, and Mr. Edward Rochester, master of Thornfield Hall, makes for some wonderfully gripping (and, dare I say, romantic?) reading.

~Ann, Adult Services

Sunday, May 1, 2016

Staff Review: My Name Is Lucy Barton by Elizabeth Strout

My Name Is Lucy Barton is the third novel I've read by Elizabeth Strout. I began reading her in 2008 when she published Olive Kitteridge, which won the 2009 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and became an HBO four-part mini-series starring Frances McDormand.

I'm always a little puzzled by my relationship with this author. Her characters sometimes put me off with their razor-sharp tongues, relentless sarcasm, and the cloying dysfunction within which they live, and yet there is also something so compelling about her novels that I find myself reading her again.

So, what is it? In part it's her intelligence and in part her settings -- I love stories that unfold in New England. She's also a wonderful wordsmith. Her novels revolve around families, their interactions, traumas, and flaws.

In Strout's newest novel, Lucy Barton comes from a poverty-stricken, emotionally-crippled family, a family that frequently goes hungry and lives without benefit of heat, books, television, decent clothes, and any normal displays of affection. When her parents go out, they lock little Lucy in a truck at home, one time, inadvertently, with a snake.

Lucy manages to break away from her unlovely kin via college and an interest in writing. Years later, as a young wife and mother, she finds herself stuck in a hospital for weeks with an unspecified infection. To her great surprise, her estranged mother shows up and camps out in Lucy's room, and the two spend hours talking, gossipy talk mostly, about people from the past. Her mother then leaves and the uncharacteristic bonding's over. While it lasts though, Lucy's in deep mother-love and happy.

Strout's achievement in this short novel is her very human understanding, her compassion for Lucy's badly flawed family members, who made her childhood such a misery, and her realistic offering of an alternate way of life. As a Boston Globe reviewer notes in her glowing review: The "psychic wounds of her childhood are part of Lucy, but they do not define her. We see this as we watch her find her place in the world, learn how to be ruthless for her art, and come to understand that while humiliation is unacceptable, humility is essential."

~Ann, Adult Services

I'm always a little puzzled by my relationship with this author. Her characters sometimes put me off with their razor-sharp tongues, relentless sarcasm, and the cloying dysfunction within which they live, and yet there is also something so compelling about her novels that I find myself reading her again.

So, what is it? In part it's her intelligence and in part her settings -- I love stories that unfold in New England. She's also a wonderful wordsmith. Her novels revolve around families, their interactions, traumas, and flaws.

In Strout's newest novel, Lucy Barton comes from a poverty-stricken, emotionally-crippled family, a family that frequently goes hungry and lives without benefit of heat, books, television, decent clothes, and any normal displays of affection. When her parents go out, they lock little Lucy in a truck at home, one time, inadvertently, with a snake.

Lucy manages to break away from her unlovely kin via college and an interest in writing. Years later, as a young wife and mother, she finds herself stuck in a hospital for weeks with an unspecified infection. To her great surprise, her estranged mother shows up and camps out in Lucy's room, and the two spend hours talking, gossipy talk mostly, about people from the past. Her mother then leaves and the uncharacteristic bonding's over. While it lasts though, Lucy's in deep mother-love and happy.

Strout's achievement in this short novel is her very human understanding, her compassion for Lucy's badly flawed family members, who made her childhood such a misery, and her realistic offering of an alternate way of life. As a Boston Globe reviewer notes in her glowing review: The "psychic wounds of her childhood are part of Lucy, but they do not define her. We see this as we watch her find her place in the world, learn how to be ruthless for her art, and come to understand that while humiliation is unacceptable, humility is essential."

~Ann, Adult Services

Sunday, April 10, 2016

Staff Review: The Age of Ambition: Chasing Fortune, Truth, and Faith in the New China by Evan Osnos

Age of Ambition by Evan Osnos, the 2014 National Book Award winner for nonfiction, is Carnegie-Stout's adult book-discussion selection for June. The discussion will take place June 14th at 7 PM and there's a lot to discuss! Osnos presents everyday life in the new economically-booming China. His focus is on the years 2005 - 2013, which he spent in China as correspondent for The Chicago Tribune and The New Yorker magazine.

I wanted to read this book because China has dominated the news for so many years now, yet I had no real sense of what it's like to live there. We hear what sounds like good news: greater prosperity, rising standards of living, economic development, increased openness, but we also hear the bad: staggering levels of corruption, pollution, shoddy construction, economic inequality, censorship. So, what is it really like to live in China today?

Osnos is a good writer and a faultlessly objective journalist. I could detect no political ideology on his part, and he pays the same respect and attention to pro-democracy individuals that he pays to those who are strongly one-party nationalistic. He presents China more anecdotally than statistically, having conducted his research by talking to hundreds of people: interviewing individuals with a wide variety of outlooks, occupations, and incomes; building long-term relationships; traveling broadly; tracking people and issues over time. Living in the polarized political environment that constitutes the United States today, I was almost taken aback by his ability to report without bias. His narrative is fascinating, comprehensive, and human.

That said, I found the picture he paints of life in China today to be grim. A sense of oppression settled over me as I read and didn't lift until close to the end of the book, when Osnos speaks to the growing demand by the Chinese people for governmental transparency, truthful news, freedoms of information and expression, cleaner air, ethical codes of business, the right to spiritual or religious lives, and on and on. There's no doubt he is right about that growing demand, but the most recently selected governing body of the Chinese Communist Party, which he describes in the book's final chapters, gives little sign of acquiescing in any way (and, in fact, quite the opposite), and as with all authoritarian regimes, they oversee and censor all media outlets, including the Internet, and control the military, police, and weaponry. The coming years should be very interesting.

~Ann, Adult Services

I wanted to read this book because China has dominated the news for so many years now, yet I had no real sense of what it's like to live there. We hear what sounds like good news: greater prosperity, rising standards of living, economic development, increased openness, but we also hear the bad: staggering levels of corruption, pollution, shoddy construction, economic inequality, censorship. So, what is it really like to live in China today?

Osnos is a good writer and a faultlessly objective journalist. I could detect no political ideology on his part, and he pays the same respect and attention to pro-democracy individuals that he pays to those who are strongly one-party nationalistic. He presents China more anecdotally than statistically, having conducted his research by talking to hundreds of people: interviewing individuals with a wide variety of outlooks, occupations, and incomes; building long-term relationships; traveling broadly; tracking people and issues over time. Living in the polarized political environment that constitutes the United States today, I was almost taken aback by his ability to report without bias. His narrative is fascinating, comprehensive, and human.

That said, I found the picture he paints of life in China today to be grim. A sense of oppression settled over me as I read and didn't lift until close to the end of the book, when Osnos speaks to the growing demand by the Chinese people for governmental transparency, truthful news, freedoms of information and expression, cleaner air, ethical codes of business, the right to spiritual or religious lives, and on and on. There's no doubt he is right about that growing demand, but the most recently selected governing body of the Chinese Communist Party, which he describes in the book's final chapters, gives little sign of acquiescing in any way (and, in fact, quite the opposite), and as with all authoritarian regimes, they oversee and censor all media outlets, including the Internet, and control the military, police, and weaponry. The coming years should be very interesting.

~Ann, Adult Services

Tags:

Ann,

Asia,

Audiobooks,

Book Discussions,

FY16,

Non-Fiction,

Staff Reviews

Sunday, March 27, 2016

Staff Review: The Expatriates by Janice Y. K. Lee

The Expatriates is Janice Y. K. Lee's second novel. (Her first, The Piano Teacher, received glowing reviews from editors if not from all readers.) This new effort is a compelling read about affluent ex-pats in bustling, present-day Hong Kong. The city is temporary home to thousands of lawyers and business-people, who, along with their families, are all benefiting quite nicely from the global economy.

Set within -- but also in stark relief against -- this backdrop of monied privilege are the troubled lives of three very different women, from whose rotating vantage point the novel is narrated.

Mercy, a young Korean-American Columbia grad, has come to Hong Kong to try to find the big, fancy job that has thus far eluded her back in the States. Hilary, a 38-year-old with a troubled, or, more accurately, receding marriage, is unable to conceive the child she so wants. Margaret, the beautiful, kind, nearly impeccable landscape architect, has left her career behind to accompany her husband to Hong Kong, where the whole family suffers a tragic event that leaves them (and this reader) reeling.

I enjoyed this novel very much. Unlike the characters in too many novels these days, these women are sympathetic, although not always entirely likable. Like all of us, they make mistakes and they pay the price. The novel resolves nicely too, in a realistic way that may not satisfy those who crave really happy endings but doesn't leave the reader at all hopeless either. The author does a wonderful job of evoking the lifestyles of those for whom Asia is both workplace and playground, while at the same time demonstrating that money is often of very little value when it comes to solving serious personal problems. In a money-mad age, we sometimes forget that last bit.

~Ann, Adult Services

Set within -- but also in stark relief against -- this backdrop of monied privilege are the troubled lives of three very different women, from whose rotating vantage point the novel is narrated.

Mercy, a young Korean-American Columbia grad, has come to Hong Kong to try to find the big, fancy job that has thus far eluded her back in the States. Hilary, a 38-year-old with a troubled, or, more accurately, receding marriage, is unable to conceive the child she so wants. Margaret, the beautiful, kind, nearly impeccable landscape architect, has left her career behind to accompany her husband to Hong Kong, where the whole family suffers a tragic event that leaves them (and this reader) reeling.

I enjoyed this novel very much. Unlike the characters in too many novels these days, these women are sympathetic, although not always entirely likable. Like all of us, they make mistakes and they pay the price. The novel resolves nicely too, in a realistic way that may not satisfy those who crave really happy endings but doesn't leave the reader at all hopeless either. The author does a wonderful job of evoking the lifestyles of those for whom Asia is both workplace and playground, while at the same time demonstrating that money is often of very little value when it comes to solving serious personal problems. In a money-mad age, we sometimes forget that last bit.

~Ann, Adult Services

Sunday, March 13, 2016

Staff Review: An Unnecessary Woman by Rabih Alameddine

An Unnecessary Woman by Rabih Alameddine is a novel like no other I have read. The book kept calling to me from the library shelf, so I finally picked it up. Rifling through it, I saw exotic references to writers, composers, artists, and philosophers, people like W.G. Sebald, Fernando Pessoa, Javier Marias, Michel Foucault, and dozens of others. Not your everyday novel. The author appears to have read vast galaxies of books.

An Unnecessary Woman by Rabih Alameddine is a novel like no other I have read. The book kept calling to me from the library shelf, so I finally picked it up. Rifling through it, I saw exotic references to writers, composers, artists, and philosophers, people like W.G. Sebald, Fernando Pessoa, Javier Marias, Michel Foucault, and dozens of others. Not your everyday novel. The author appears to have read vast galaxies of books.The story is brought to you in the first person by the unnecessary woman of the title, Aaliya, a 72-year-old solitary, long divorced, who worked all her life in a bookstore. For many of those years she also translated books into Arabic: books by Leo Tolstoy, Roberto Bolano, Italo Calvino, Knut Hamsun, Jose Saramago, and over thirty more. At the start of each year, she enjoys the quiet thrill of selecting the coming year's translation. Once the translation is finished, she boxes it up; it goes unseen and unknown by the world. Her manuscripts fill cartons and rooms.

Her highbrow literary tastes form the skeletal structure of the book. She weaves anecdotes about books and authors through her musings about her own life: her work, her habits, her "impotent insect" of an ex-husband, the manner in which she acquired her AK-47, her less than loving relationship with her mother, the suicide of her best friend.

Aaliya's colorful, acerbic, highly-opinionated narration brings Beirut, her hometown, to vivid life in all its splendor and catastrophe, for she has lived through long years of Civil War and sectarian strife (hence the bedside AK-47). Aaliya certainly knows her own mind yet she also questions a lot, she doesn't suffer fools gladly, and she definitely does not mince words.

An Unnecessary Woman is a journey through the carefully examined life of a highly intelligent and peppery woman, an outwardly unremarkable woman who has lived her whole life for the love of literature, language, music, art, and ideas. And, as a bonus, the novel ends on a genuinely uplifting note.

~Ann, Adult Services

Sunday, February 21, 2016

Staff Review: The Rocks by Peter Nichols

The quirk (and at times this reader's confusion) with the book is that it unfolds backwards through time, opening in 2005 with a big splash (literally) and then moving into the past in increments, all the way back to 1948. The Rocks of the title is a lovely hotel perched over the water on the coast of Mallorca. Its proprietress, a commanding woman named Lulu, has been running the hotel for decades and serves as hostess to a tight-knit group of more or less degenerate ex-pats. The arc of her life and its early, brief intersection with the life of a Homer-loving islander named Gerald form the central plot of the novel. Lulu and Gerald each have a child, a boy and a girl whose lives intersect throughout, and their stories are told too.

Few of the novel's characters are entirely likable and the preponderance of missed opportunities, misunderstandings, failures, and sad regrets may wear on the reader's patience and psyche. What kept me going was not only the fabulous Steve West but also the way the book vividly re-creates its times and places -- Mallorca present-day or Morocco in the seventies, for example -- and the genuine voices of the island's denizens, which rarely hit a false note, whether it's a lecherous old has-been rambling on and on, the village police chief, the shop-owner who sells Gerald's almonds and olives, or Gerald himself, gentleman and scholar. The achievement of the book is that even while you're put off by the characters' decadence, or triviality, you still kind of wish you were lying on a sun-bleached rock among them, ocean beside you, sangria in hand.

~Ann, Adult Services

Sunday, February 7, 2016

Staff Review: Stoner by John Williams

A 2013 review of the novel Stoner in The New Yorker magazine was titled "The Greatest American Novel You've Never Heard Of." I received a copy of the book for Christmas, read it right away, and was happy to see that the library owns it too.

Originally published in 1965, Stoner, by John Williams, sold an anemic 2000 copies and was quickly forgotten. Re-published in the new millenium, it was soon translated into French, becoming a best-seller across Europe. That enthusiasm traveled back to the U.S and Stoner now seems likely to be considered at least a minor classic.

Originally published in 1965, Stoner, by John Williams, sold an anemic 2000 copies and was quickly forgotten. Re-published in the new millenium, it was soon translated into French, becoming a best-seller across Europe. That enthusiasm traveled back to the U.S and Stoner now seems likely to be considered at least a minor classic.

The book's title refers to the main character, William Stoner, a pre-World War I-era farm boy whose joyless, wordless, utterly wrung-out parents wish him to prepare to assume the family farm by studying agriculture at the University of Missouri. In a literature class there one day, the heavens part and Stoner has an almost-religious epiphany, glimpsing the beauty and wisdom to be found in books. Abruptly changing majors, he ultimately earns a PhD, becomes a professor at the college, and teaches there for the rest of his life.

So far, so good, except that every other area of Stoner's life gradually becomes so difficult that the book can be tough to read. In his naïveté, he marries a cold young woman in haste and repents at leisure right up to his death bed. His beloved young daughter becomes estranged from him through the sadistic maneuverings of his wife. Cruel and peculiar college politics prevent his ever being promoted.

If the book is beginning to sound unrelievedly grim, it's not. It's a close-up look at an ordinary life. There are compensations and redemptions. Stoner is a sort of Everyman: fairly unremarkable, quiet, passive; one reviewer refers to him as the anti-Gatsby. But he's also genuinely and wonderfully free of neurosis and of so many less attractive human traits: envy, vindictiveness, anger, resentment, self-pity. The cover of the reissued book admirably portrays his character.

The beauty of this novel lies not only in the prose, where not a word seems wasted, but also in Stoner's day-to-day, clear-eyed sanity, the quiet and committed calm of the man as he navigates a typically turbulent life. It's as though his steadfast devotion to teaching and his unswerving faith in art allow him to exist relatively undisturbed above the fray. Stoner is a tribute to the literary life and to the sustaining power of an earnest vocation.

~Ann, Adult Services

Originally published in 1965, Stoner, by John Williams, sold an anemic 2000 copies and was quickly forgotten. Re-published in the new millenium, it was soon translated into French, becoming a best-seller across Europe. That enthusiasm traveled back to the U.S and Stoner now seems likely to be considered at least a minor classic.

Originally published in 1965, Stoner, by John Williams, sold an anemic 2000 copies and was quickly forgotten. Re-published in the new millenium, it was soon translated into French, becoming a best-seller across Europe. That enthusiasm traveled back to the U.S and Stoner now seems likely to be considered at least a minor classic. The book's title refers to the main character, William Stoner, a pre-World War I-era farm boy whose joyless, wordless, utterly wrung-out parents wish him to prepare to assume the family farm by studying agriculture at the University of Missouri. In a literature class there one day, the heavens part and Stoner has an almost-religious epiphany, glimpsing the beauty and wisdom to be found in books. Abruptly changing majors, he ultimately earns a PhD, becomes a professor at the college, and teaches there for the rest of his life.

So far, so good, except that every other area of Stoner's life gradually becomes so difficult that the book can be tough to read. In his naïveté, he marries a cold young woman in haste and repents at leisure right up to his death bed. His beloved young daughter becomes estranged from him through the sadistic maneuverings of his wife. Cruel and peculiar college politics prevent his ever being promoted.

If the book is beginning to sound unrelievedly grim, it's not. It's a close-up look at an ordinary life. There are compensations and redemptions. Stoner is a sort of Everyman: fairly unremarkable, quiet, passive; one reviewer refers to him as the anti-Gatsby. But he's also genuinely and wonderfully free of neurosis and of so many less attractive human traits: envy, vindictiveness, anger, resentment, self-pity. The cover of the reissued book admirably portrays his character.

The beauty of this novel lies not only in the prose, where not a word seems wasted, but also in Stoner's day-to-day, clear-eyed sanity, the quiet and committed calm of the man as he navigates a typically turbulent life. It's as though his steadfast devotion to teaching and his unswerving faith in art allow him to exist relatively undisturbed above the fray. Stoner is a tribute to the literary life and to the sustaining power of an earnest vocation.

~Ann, Adult Services

Sunday, January 17, 2016

Staff Review: The Winter People by Jennifer McMahon

The Winter People weaves two time-frames together: the very early 1900s and the present day, both narratives unfolding in the same place: the village of West Fall, Vermont, which should be idyllic but is actually totally creepy. In 1908, West Fall farm wife Sara Harrison Shea, in deep mourning over her small daughter's recent death, is brutally murdered and then skinned, a horrific crime that has never been solved.

Fortunately, Sara left behind a journal, which not only chronicles life's (mostly tragic) events but also describes in detail the phenomenon of "the sleepers," dead people allegedly brought back to life, who may haunt the wooded crags near West Fall, particularly the area of outcroppings known as the Devil's Hand. Sara's journal was so sensational that it was published after her death, under the title Visitors from the Other Side.

One hundred years later, the present-day occupants of Sara's old farmhouse, the Washburn family, find themselves swept up in the mystery of Sara's death and the sleepers. This is no coincidence, because the parents had learned of Sara and her journal before moving to Vermont and, in fact, purchased the Shea farmhouse in an attempt to locate missing journal pages that set out the exact steps involved in raising the dead. The Washburns' hope is to cash in on that secret knowledge, for who that has experienced traumatic loss would not pay good money to resurrect a beloved partner or child? This book is populated with people possessed of this desire.

I won't say much more because The Winter People is such a fun, compelling read because of its building suspense: what is real, what is the product of overwrought imagination, what is only a dream? The truth is ever-so-slowly revealed as the narratives move back and forth between the unfolding revelations of Sara's diary and the present-day search by the two Washburn daughters for their mother, who has suddenly and inexplicably disappeared. A constant presence in both stories, the Devil's Hand looms dark and terrifying, its rocks, caves, and deep-forest trees shrouding all manner of things that go bump -- or scuttle-scuttle -- in the night.

~Ann, Adult Services

Saturday, December 26, 2015

One of the Best Books I Read in 2015: Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates

I'm just now concluding my third -- yes, third -- consecutive listen to the audiobook Between the World and Me, written and read by Ta-Nehisi Coates. The book has been receiving a lot of sometimes-controversial buzz and some big awards ever since its publication in July of this year, and it is now popping up on all sorts of year-end "Best of" lists. I decided I better check it out, but I was wholly unprepared for its enormous impact on me.

The book is written in the form of a letter from the author to his 15-year-old son Samori, and its subject is living in a black body in a country built on slave labor and too often disposed toward the destruction of those bodies. Coates grew up in a gritty neighborhood of Baltimore, where the streets, his family, the police, and even the schools inculcated in him a pervasive sense of fear. A curious young man, he set out to "interrogate" his situation, turning to books, professors, poetry, and his own journalistic writing to make sense of the world. And what a stunning job he does of the making-sense.

Learning to write is learning to think, Coates contends, and his mastery of both is evident on every page. This book is so very intelligent -- and honest, sad, perceptive, poetic, profound, and radical. Its 176 pages are suffused with one thoughtful 40-year-old man's meticulously-examined life and hard-won wisdom. It is not a hopeful book, but it is not despairing either. What it is is truly counter-cultural and these days that's so rare.

~Ann, Adult Services

The book is written in the form of a letter from the author to his 15-year-old son Samori, and its subject is living in a black body in a country built on slave labor and too often disposed toward the destruction of those bodies. Coates grew up in a gritty neighborhood of Baltimore, where the streets, his family, the police, and even the schools inculcated in him a pervasive sense of fear. A curious young man, he set out to "interrogate" his situation, turning to books, professors, poetry, and his own journalistic writing to make sense of the world. And what a stunning job he does of the making-sense.

Learning to write is learning to think, Coates contends, and his mastery of both is evident on every page. This book is so very intelligent -- and honest, sad, perceptive, poetic, profound, and radical. Its 176 pages are suffused with one thoughtful 40-year-old man's meticulously-examined life and hard-won wisdom. It is not a hopeful book, but it is not despairing either. What it is is truly counter-cultural and these days that's so rare.

~Ann, Adult Services

Tags:

Ann,

Audiobooks,

Books,

FY16,

Memoir,

Non-Fiction,

Staff Reviews

Sunday, November 15, 2015

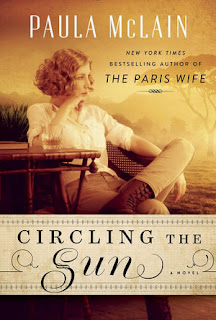

Staff Review: Circling the Sun by Paula McLain

Circling the Sun is an exhilarating novel -- author Paula McLain has done it again. Her second book, The Paris Wife, published in 2011, told the novelized story of Ernest Hemingway's ill-fated first marriage, to Hadley Richardson, a story that played out among the brilliant ex-pat community known as the Lost Generation in Paris in the 1920s. The Paris Wife quickly became a bestseller.

This time round, McLain tackles the life of aviator Beryl Markham, who told her story herself in her marvelous memoir West with the Night, a book that Hemingway, incidentally, referred to as "bloody wonderful."

Beryl Markham was born in England in 1902 and moved to Kenya (then British East Africa) as a tiny girl. Her mother was unable to handle life in Africa and soon fled with Beryl's older brother, leaving Beryl in her father's care for good. This unusual and tragic abandonment had a silver lining: it seems to have liberated Beryl from most of the rigid restrictions and tiresome conventions placed upon girls in affluent British families. Instead Beryl literally ran wild, which makes for one invigorating story.

Have I mentioned yet that Beryl was also beautiful and loved to party? She hobnobbed with all the British colonials, including the uber-hedonistic Happy Valley set, whose drinking, drug use, and promiscuity have become the stuff of legend. Beryl herself married three times, disastrously, and had countless lovers throughout her life. The love of her life was Denys Finch Hatton, the aristocratic big-game hunter and not-so-secret paramour of the writer Isak Dineson (played by Meryl Streep to Robert Redford's Finch Hatton in the 1985 film Out of Africa).

This review cannot even begin to describe the adventurous, ambitious life of Beryl Markham. My only quibble with the novel is that it airbrushes some of Beryl's less admirable qualities. In real life she suffered for them though: she was often embroiled in scandal, she never received her due acclaim, and her final days saw her living in poverty. My caveat to readers is that references to safaris, lion hunting, ivory expeditions -- indeed to so many things decadent, exploitative, and colonial -- can be hard to take. But this was the (waning) age of imperialism and of the Great White Hunter (in the U.S. Teddy Roosevelt had recently been president) and it must have seemed at the time that Brittania still ruled and that Africa's wildlife was endless.

~Ann, Adult Services

This time round, McLain tackles the life of aviator Beryl Markham, who told her story herself in her marvelous memoir West with the Night, a book that Hemingway, incidentally, referred to as "bloody wonderful."

Beryl Markham was born in England in 1902 and moved to Kenya (then British East Africa) as a tiny girl. Her mother was unable to handle life in Africa and soon fled with Beryl's older brother, leaving Beryl in her father's care for good. This unusual and tragic abandonment had a silver lining: it seems to have liberated Beryl from most of the rigid restrictions and tiresome conventions placed upon girls in affluent British families. Instead Beryl literally ran wild, which makes for one invigorating story.

When small, Beryl played freely in the African wilderness with her close friend Kibii of the Kipsigis tribe and received almost no formal education. She hunted warthogs barefoot with a spear, attended tribal dances, and was mauled by a lion. Her father bred and trained horses at their farm in Kenya, and horses became Beryl's passion too. Before she was 20, she became the first licensed female racehorse trainer in Kenya, and at age 34 she became the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic and the first person to do so nonstop east to west.

Have I mentioned yet that Beryl was also beautiful and loved to party? She hobnobbed with all the British colonials, including the uber-hedonistic Happy Valley set, whose drinking, drug use, and promiscuity have become the stuff of legend. Beryl herself married three times, disastrously, and had countless lovers throughout her life. The love of her life was Denys Finch Hatton, the aristocratic big-game hunter and not-so-secret paramour of the writer Isak Dineson (played by Meryl Streep to Robert Redford's Finch Hatton in the 1985 film Out of Africa).

This review cannot even begin to describe the adventurous, ambitious life of Beryl Markham. My only quibble with the novel is that it airbrushes some of Beryl's less admirable qualities. In real life she suffered for them though: she was often embroiled in scandal, she never received her due acclaim, and her final days saw her living in poverty. My caveat to readers is that references to safaris, lion hunting, ivory expeditions -- indeed to so many things decadent, exploitative, and colonial -- can be hard to take. But this was the (waning) age of imperialism and of the Great White Hunter (in the U.S. Teddy Roosevelt had recently been president) and it must have seemed at the time that Brittania still ruled and that Africa's wildlife was endless.

~Ann, Adult Services

Sunday, November 8, 2015

Staff Review: Kitchens of the Great Midwest by J. Ryan Stradal

Many readers are calling J. Ryan Stradal's debut novel Kitchens of the Great Midwest "quirky." The way I'd describe it -- and a reader's possible reaction to it -- is this: it may not be your cup of tea if you love linear plots, character development, and satisfying resolutions. On the other hand, you may love it if you're open to vivid vignettes, you love eating (and reading about) food, and you have a big, broad sense of humor. Living in the northern Midwest (in Dubuque, for instance) will dispose you toward it too.

Although labeled a novel, Kitchens more closely

resembles a set of linked stories, in the first half of which Eva

Thorvald, the protagonist, is a child.

Eva is gifted with an exceptional palate and through the course of the

book's twenty years becomes the most celebrated chef in America, one

whose exquisite dishes are available only through highly-sought-after,

ticketed dinners at venues across the U.S. The second half of the book

circles around Eva more distantly, through the exquisitely-portrayed

(and sometimes skewered) lives of a large cast of secondary characters.

Although labeled a novel, Kitchens more closely

resembles a set of linked stories, in the first half of which Eva

Thorvald, the protagonist, is a child.

Eva is gifted with an exceptional palate and through the course of the

book's twenty years becomes the most celebrated chef in America, one

whose exquisite dishes are available only through highly-sought-after,

ticketed dinners at venues across the U.S. The second half of the book

circles around Eva more distantly, through the exquisitely-portrayed

(and sometimes skewered) lives of a large cast of secondary characters.

Although there were a couple times early on when I considered dropping the book altogether (one chapter in particular just seemed too dark and too mean), I soldiered on and I'm so glad I did. I soon found myself laughing out loud, recognizing fictional characters that matched (to a T) individuals I'd known in Wisconsin, and marveling at the heartfelt poignance of some of the scenes. Originally from Minnesota, Stradal is a confident debut writer, maybe because writing is just one thing he does well (he's also a TV producer who knows a bit about food and a whole lot more about wine -- food and wine pairings feature prominently in the novel).

Although labeled a novel, Kitchens more closely

resembles a set of linked stories, in the first half of which Eva

Thorvald, the protagonist, is a child.

Eva is gifted with an exceptional palate and through the course of the

book's twenty years becomes the most celebrated chef in America, one

whose exquisite dishes are available only through highly-sought-after,

ticketed dinners at venues across the U.S. The second half of the book

circles around Eva more distantly, through the exquisitely-portrayed

(and sometimes skewered) lives of a large cast of secondary characters.

Although labeled a novel, Kitchens more closely

resembles a set of linked stories, in the first half of which Eva

Thorvald, the protagonist, is a child.

Eva is gifted with an exceptional palate and through the course of the

book's twenty years becomes the most celebrated chef in America, one

whose exquisite dishes are available only through highly-sought-after,

ticketed dinners at venues across the U.S. The second half of the book

circles around Eva more distantly, through the exquisitely-portrayed

(and sometimes skewered) lives of a large cast of secondary characters. Although there were a couple times early on when I considered dropping the book altogether (one chapter in particular just seemed too dark and too mean), I soldiered on and I'm so glad I did. I soon found myself laughing out loud, recognizing fictional characters that matched (to a T) individuals I'd known in Wisconsin, and marveling at the heartfelt poignance of some of the scenes. Originally from Minnesota, Stradal is a confident debut writer, maybe because writing is just one thing he does well (he's also a TV producer who knows a bit about food and a whole lot more about wine -- food and wine pairings feature prominently in the novel).

In the funniest

parts, Stradal pokes gentle fun at Midwestern county-fair-bake-sale participants (who apparently haven't changed much since the fifties), but also at those

hyper-fastidious eaters within the new food culture who are more obsessed with

what they can't or won't eat than with what they can or will. A New

York Times reviewer points

out in a positive review that describes Kitchens as

"a gastronomic portrait of a region," that "Stradal reserves his

most gleeful satire for the overwrought foodies who rock back and forth in

their chairs, weeping and licking their dishes, in response to a $5,000-a-plate

dinner for which they’ve spent four years on the waiting list."

So, set aside

any pre-conceived notions of what a novel should be and hop aboard for this

fun, fast-moving ride. You may even decide to read the book twice, as the large

cast of characters who re-appear only after the passage of many pages and years can be tricky

to keep track of first time 'round (the book ought to come with a schematic). I wouldn't

want to read book after book structured this way, but like the occasional gooey dessert, this book was pretty delicious.

~Ann, Adult Services

~Ann, Adult Services

Sunday, October 18, 2015

Staff Review: A Trio of Recent(ish) Novels

I am woefully behind in my fiction reading, an

unfortunate situation caused, in part, by a long detour into Nonfictionland.

In an attempt to catch up, I just blew through a trio of novels I missed over the past two or three years.

My favorite was The Burgess Boys by Elizabeth Strout (of Olive Kitteridge fame), which tells the story of three adult

siblings from a Maine family racked by a tragic childhood event (one of the three accidentally killed their father in an incident relayed in the novel's first pages). Oldest son Jim